The Key to Mastery Expert Photographers Know (that you don’t)

Malcolm Gladwell once famously said:

“It takes ten thousand hours to truly master anything. Time spent leads to experience; experience leads to proficiency; and the more proficient you are the more valuable you’ll be.”

Since then, this “10,000 Hours Rule” has become immensely popular.

It’s been passed around in literature, blogs, forums, and the rule has been expanded to many other fields.

But a lot of people actually misinterpret the meaning of this concept.

Today I want to clear things up about the 10,000 Hours Rule, how I use it in my photography practice, and how you can take and apply it to your creative journey.

Let’s begin.

What People Get Wrong

Why do people get the 10,000 Hours Rule wrong?

The simple reason is because they hear the number and extract what they want from it.

Most people hear 10,000 hours and think:

it’s a hard and fast number (than anything less or more doesn’t count)

talent doesn’t play a role (only the hours do)

they can clock in and clock out and it’ll be worth the same

So a lot of people will grind trying to reach 10,000 without ever thinking about how they’re grinding.

This isn’t to say that volume isn’t important - it obviously is.

Just that there’s more to this concept than just volume.

Originally, the number came from studies of chess masters in the 20th century, where many of them took roughly 10 years to reach a level of mastery.

But nowadays there are many cases where we’d see “mastery” at less than 10,000 hours, because things like online learning are much more efficient now.

Even Gladwell himself was surprised with how people had reacted and interpreted what he said.

Later he mentioned:

“The number is not hard and fast - it symbolizes the fact that the time necessary to develop your innate abilities is probably longer than you think.”

He also tried to emphasize that the quality of practice does matter.

Deliberate intentional practice, improving areas of weakness, spending your time in a focused manner all make a difference.

Because obviously you can’t just run the clock, meander, and expect to get the same level of improvement.

It’s just most people hear “10,000” and forget everything else.

Similarly talent, although fixed and unequal can definitely influence your growth over the long term.

A more talented person or someone who’s better at learning might find mastery quicker or easier to attain.

Now it’s of my opinion that talent shouldn’t be the thing we focus on (because we can’t really change it), but I won’t deny it’s influence.

In essence, here are 4 things you should keep in mind when thinking about photography mastery:

First, 10,000 hours is not hard and fast.

Meaning for some it could take less and for some it could take more.

Similarly, any number below 10,000 is still worth something.

If you dial in 5,000 or 1,000 hours, you won’t be a master, but maybe you’ll be an expert - and that’s still worth something.

We shouldn’t think about mastery as “master” or “not master”.

But rather a spectrum or continuum of mastery with a bunch of stuff in between. (more on this later).

Second, both talent and hard work make a difference.

But since talent is fixed, it becomes pointless to fixate on.

Focus on the work you have to do more than your efficiency and don’t look at others with envy and assume they’re simply better than you.

Third, quality of hours matters.

If you waste your 10,000 hours doing unserious, nonintentional, and unfocused practice, your results will reflect that.

In those cases, mastery might take you 20,000 hours instead.

On the contrary, if you find ways of practice that can compress growth, where you learn a ton in a short span of time, mastery could only take you 5,000 hours.

Or it could mean a less intense long term approach to photography - because you’re effective and efficient with your time.

Whichever you prefer.

Fourth - consistency is the most important thing here.

You can’t do 10,000 hours in one go.

Divided over the course of 10 years, that’s roughly 2.74 hours of deliberate practice a day.

That doesn’t happen on it’s own and it doesn’t happen overnight.

So learning to be consistent with whatever you do is the most important because it’s how we actually reach these larger numbers.

Doing a little consistently adds up more than doing a lot once in a while.

So, now that we know all of this, how should we approach mastery in photography?

Well, I can’t tell you the best method, but I’ll tell you what I’m doing.

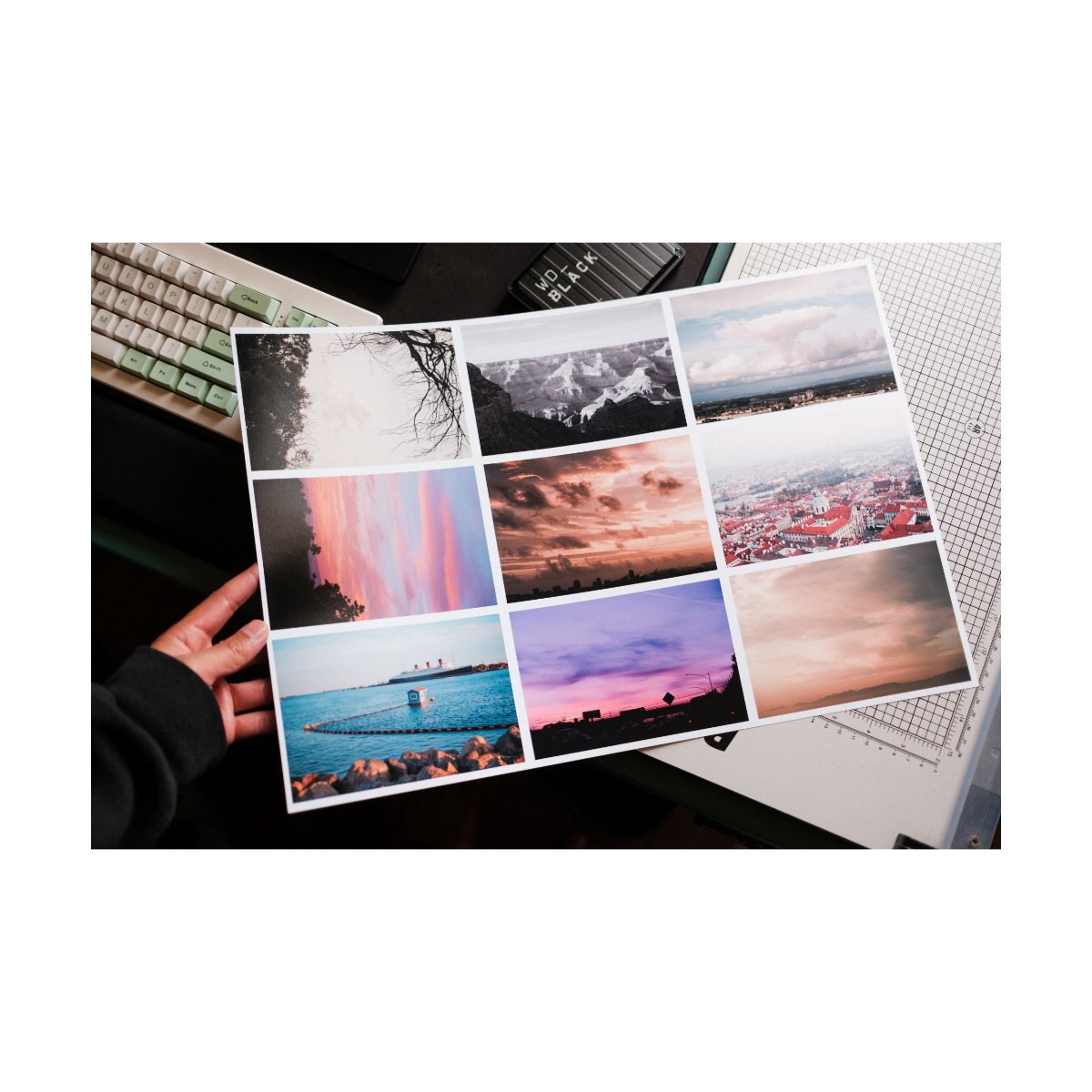

10,000 Iterations

Although 10,000 Hours is a useful concept to get us to do more, it’s not without it’s flaws.

Because of this, I prefer to look at mastery in a different way.

That’s: 10,000 Iterations.

What’s an iteration?

An iteration, as defined by the dictionary, is the repetition of a process or utterance.

Which might sound a little confusing.

I like to think of an iteration like every instance you tried something.

For example, writing a book requires multiple drafts.

Every draft could be considered an iteration.

If you’re a scientist, every hypothesis requires multiple experiments.

Every individual test you do is an iteration.

And for photographers this can vary.

An iteration can be considered every new shot you try, every draft of a photobook, every individual photo edit, etc.

This could mean that one individual photo session could contain 100 iterations or just one.

It’s different than “10,000 Hours” because how we spend our time is different.

And 10,000 Iterations could take longer or shorter than 10,000 Hours.

Iterations aren’t time based, they’re task based.

I find that the 10,000 Iterations perspective solves the problem of “quality time” we mentioned earlier.

With the 10,000 Hours concept, it didn’t matter how we spent our time.

We could sit around and stare at the computer screen and not edit anything.

We could walk around and snap at random stuff unintentionally.

We could clock in and clock out and “become a master”, which didn’t make much sense.

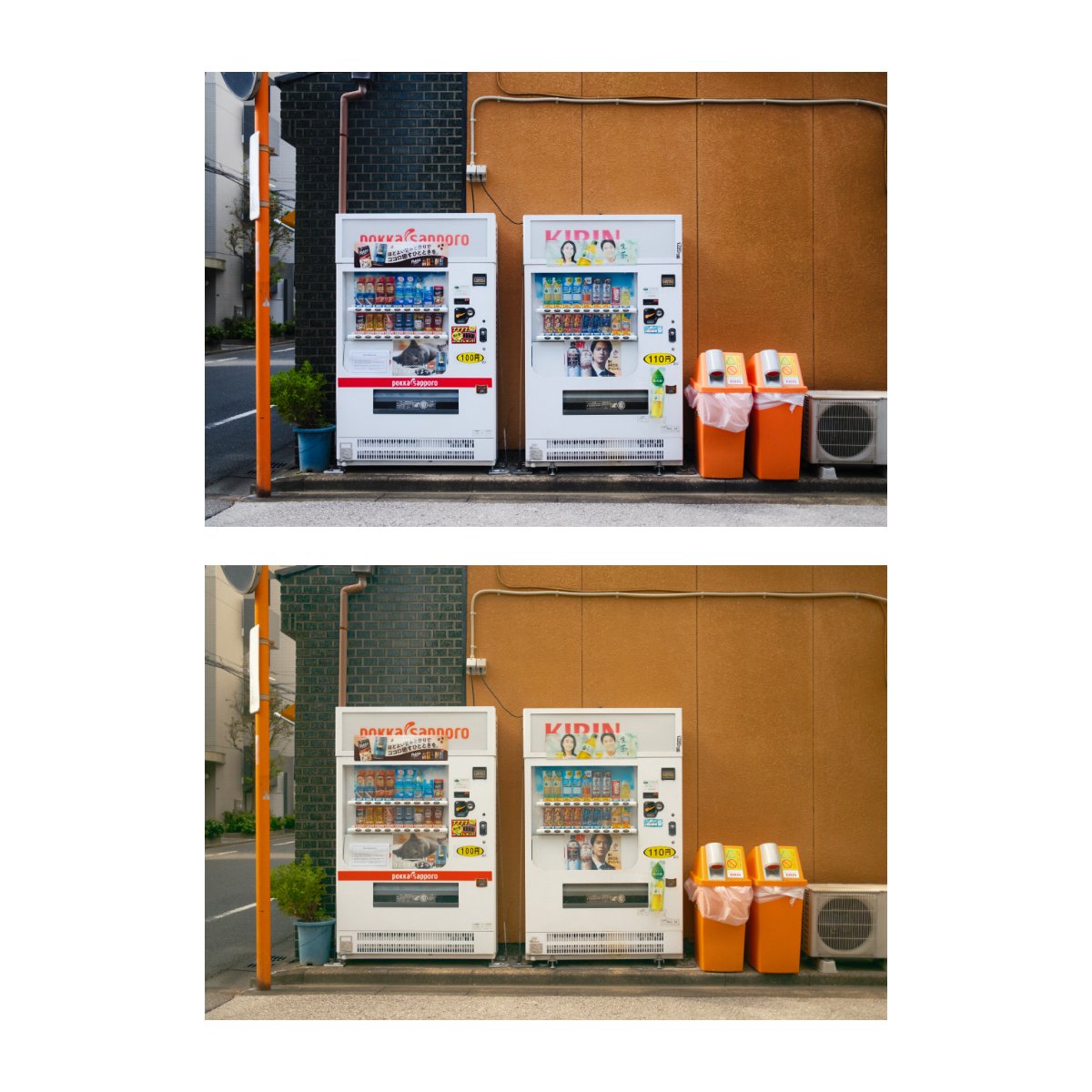

Iterations on the other hand, you have to variate.

Every new instance requires tweaking something in the formula, trying something new, trying something again to get it right this time.

And if you think about progress in creativity as the process of figuring out how to do stuff right and how not to do stuff wrong, this lines up perfectly with that.

It forces us to be accountable for how we spend our time.

And it means that the better we get at practicing itself, the quicker we can reach mastery.

Now, 10,000 Iterations not only solves the quality problem, but is also hyper effective for how creatives learn.

I mentioned in a previous article that the key to getting better at photography is trial and error.

The best artists, musicians, and inventors didn’t just do one thing the whole time.

And they certainly didn’t learn everything they knew from someone else.

Rather, many of them learned what they knew by accident.

Trying something out, failing or succeeding, and figuring something out in the process.

By orienting ourselves towards 10,000 Iterations, not hours, we can focus on what truly contributes to our growth (experimenting).

We’re not just doing the same thing over and over again.

As opposed to wandering aimlessly, we have a prompt, something new to try, some kind of shot in mind, etc.

That makes us better long term and might mean mastery in less than 10,000 Iterations.

Because so long as we’re iterating, we’re learning.

This is why I mention in Photography Systems that the way to make real progress is through trial and error and iteration.

And the way we reach 10,000 Iterations is by creating systems around us that make it natural for us to iterate as a lifestyle, which makes improving our photography inevitable.

It’s just, that’s not the answer most people want.

Everyone wants you to tell them how to take a picture or know the camera you use but…that just won’t help you become a better photographer.

However, if you change the way you look at progress in photography, start orienting your actions around that, and start listening to the feedback the world gives you, it’ll be hard not to get better.

If you’re struggling to improve your photography, you need to learn and apply this process, and change will occur.

Because doing the same thing over and over again will just give you the same result.

Sometimes each iteration will take you longer than an hour, but it’ll also teach you so much more.

The number as a whole is kind of arbitrary, whereas the magnitude is the real lesson.

In short: just get out there, keep trying new things, keep failing, and continue to do it.

Mastery Isn’t the Goal

Now that we understand the problems with the 10,000 Hours concept and how we should approach progress instead, is it still a good idea to try and become a master?

Well it’s of my opinion that mastery, although it sounds nice, shouldn’t be the goal.

Why, you might ask?

Well to keep it simple, I think of mastery as a byproduct, not a destination.

You see, a lot of people look at mastery like a place to get to.

“I want to become a master so I can do such and such, make so and so, and be looked at in a certain way.”

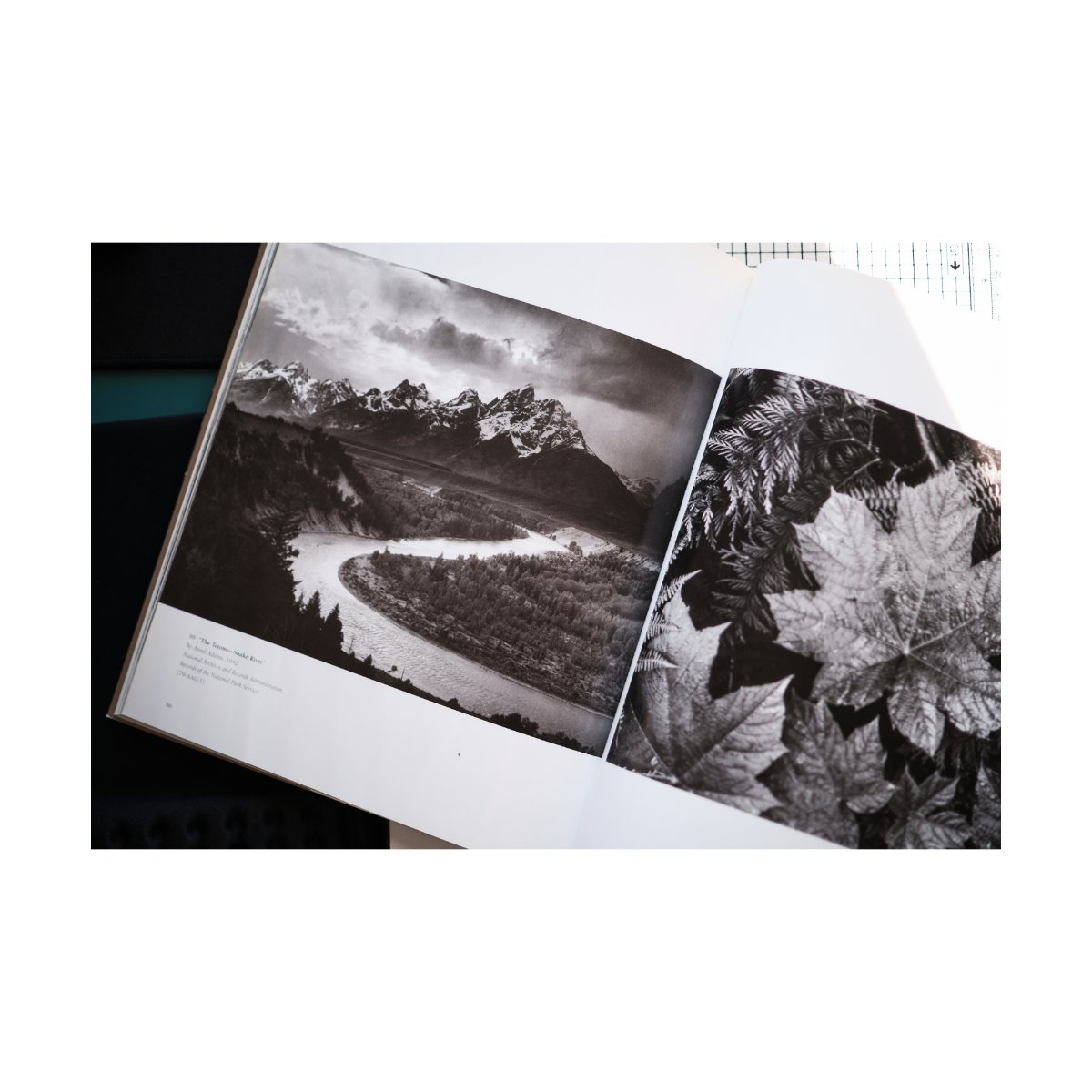

But if you study the actual masters, whether it be artists like Da Vinci, Picasso, or photographers like Cartier Bresson and Tony Vacarro, for them, mastery wasn’t the goal.

Rather they were always focused on what they were doing with their art, what they were trying to express, what they were trying to document.

This isn’t to say you can’t want to be a master, just that focusing too hard on “mastery” will orient you incorrectly.

For example, who do you think will take better photos:

The photographer who takes pictures with skill or mastery in mind or the photographer who’s focused on capturing the moment, encapsulating or expressing something relevant or unique?

I’d argue the second one, because counter intuitively you don’t always need a complex shot for it to be a good photo.

And a lot of great photos are actually very simple, they’re just of something iconic or capture that exact moment very well.

I’m sure Cartier Bresson wasn’t thinking about mastery when he prowled the streets of Paris - he was focused on capturing and documenting life there.

I’m sure Ansel Adams wasn’t thinking about mastery when he went to photograph Half Dome and Yosemite.

They were focused on the photo itself and the things they were trying to capture.

But I’d consider them masters, and they became so in the process of making the work.

So in my opinion, “mastery” has us focused on the wrong things in photography and can lead to worse results.

Whereas if you just ask yourself “what am I trying to capture?” and “how can I capture it well?”, you’ll get more shots that do the moment justice.

And when you get really good at that, who knows, people might look back at your photos and see you as a master.

But it’s not because you tried to become as master - it’s because you did what photographers were supposed to do.

And mastery was simply a byproduct of doing photography well.

Make sense?

Furthermore, focusing on mastery will work against us psychologically.

10,000 Iterations is a lot of iterations.

And if you’re focused on reaching that number, anything below that feels like less.

But like we mentioned earlier, mastery is a spectrum and there’s a lot of value in between.

Along the journey you’ll reach intermediate, advanced, expert, etc.

Which all have value, but if you’re focused on “master”, you lose sense of that.

So for our mental health as well, zooming in and keeping focus on just what we do everyday is a preferred method.

We’re not going to climb that mountain all at once, so let’s just do a little every day.

It’ll all add up in ways we won’t notice now, but will see later.

In the long spam of things mastery becomes an arbitrary word to describe something that doesn’t matter.

Because who cares if you’re a “master”? - the real question is “what have you made and what are you making?”

That seems to be a more realistic and peaceful way to go about our creative journeys.

So hopefully you found this helpful and now know how you want to orient your creative journey.

If you want to learn more about improving your photography, shoot more and stress less, check out Photography Systems.

It’s where we cover all of the psychology and doing of the craft.

If you found this useful, I think you’ll find that useful.

Thanks for reading, happy shooting.