Photography Advice I Learned From Studying the Greats

There are no new answers.

That’s an important lesson I try to remind myself in my photography journey and just life in general.

It’s often the very problems we struggle with have already been solved by those who’ve come before us.

And even if we feel like we’ve found a new or true insight, someone’s probably said it already.

So why then, do we struggle instead of simply picking up a book, read what the masters have already found in their lifetime of learning, and apply it to our craft?

Perhaps it’s a time thing - as time passes we forget.

Perhaps it’s a ignorance thing - we refuse to learn from others because we think we know best.

Perhaps it’s a pride thing - we find value in learning and discovering things for ourselves.

But at the end of the day, if you’ve got a problem you have two options:

You can try to figure it out yourself or you can learn from someone who’s already solved it.

Today we’re going to do the latter.

This is photography advice I learned from studying the greats.

Cartier-Bresson and The Golden Rule

Perhaps one of the most renowned street photographers of the last century, Cartier Bresson taught us many things about photography people nowadays forget.

He popularized the concept of “The Decisive Moment”, suggesting that there’s a “decisive moment” at every interval of life and it’s the photographer’s job to capture that.

It’s a combination of anticipation, timing, and understanding that goes into capturing timeless photos.

And it’s why photography stands out from other mediums - the frame frozen in time can tell a thousand words.

It’s ironic then, that I still see photographers today struggling and misunderstanding many of the concepts Cartier Bresson broke down decades ago.

I’m going to read out an excerpt from his essay “The Decisive Moment” and you see if you can catch what I’m referencing.

“Composition must be one of our constant preoccupations, but at the moment of shooting it can stem only from our intuition, for we are out to capture the fugitive moment, and all the interrelationships involved are on the move. In applying the Golden Rule, the only pair of compasses at the photographer's disposal is his own pair of eyes. Any geometrical analysis, any reducing of the picture to a schema, can be done only (because of its very nature) after the photograph has been taken, developed, and printed – and then it can be used only for a post-mortem examination of the picture. I hope we will never see the day when photo shops sell little schema grills to clamp onto our viewfinders; and the Golden Rule will never be found etched on our ground glass.”

There is much to be dissected here.

But here’s what he’s saying in pretty clear English:

composition is important but it comes from our intuition

to apply the Golden Rule, we can only use our eyes

geometrical analysis is done after the fact, not before or during the photo

What does this mean?

This means: don’t mathematicize photography!

I see so many people online trying to teach composition and framing in an overly structured way.

As if to say, “If you wanna take better photos use this mathematical thing to structure your photos. Science!”

Bullshit.

This is art and that’s not how it works.

Me personally, I’ve never gone outside on a photo session, drew a Fibonacci spiral in the sky and said, “Yep, that’s a good photo”.

Never!

Like Cartier Bresson, I follow my eyes and my intuition and I analyze the shot later.

And yet, so many people are going about trying to tell others that the reason their photo works is because it follows this perfect ratio of things, and whatever nonsense.

Because they want some justification, some hard rule to qualify what makes a good photo, to stroke their ego and prove they are good photographers.

But here he is, one of the people known and famous for his use of the Golden Rule, telling us that to apply the Golden Rule we have to use our eyes, not rulers.

And any confirmation of the Golden Rule is a post processing thing - it comes AFTER the photo has been taken.

As if predicting the future, he even hopes that we’ll never see the Golden Rule on clamps or schemas to “help” people compose.

Because that’s not how it works.

Great photos don’t come from the Golden Rule.

Great photos are taken, and when analyzed, some follow the Golden Rule.

But it doesn’t come first.

Don’t mistake the chicken for the egg.

Joel Meyerowitz and Reinventing Yourself

Let’s move on to a less heated example.

Joel Meyerowitz is another street photographer, known for his photos of New York.

But midway into his photography journey, he flipped the switch and began shooting in color, on a large 8x10 format of all things.

This was a stark contrast to his usual Leica photography.

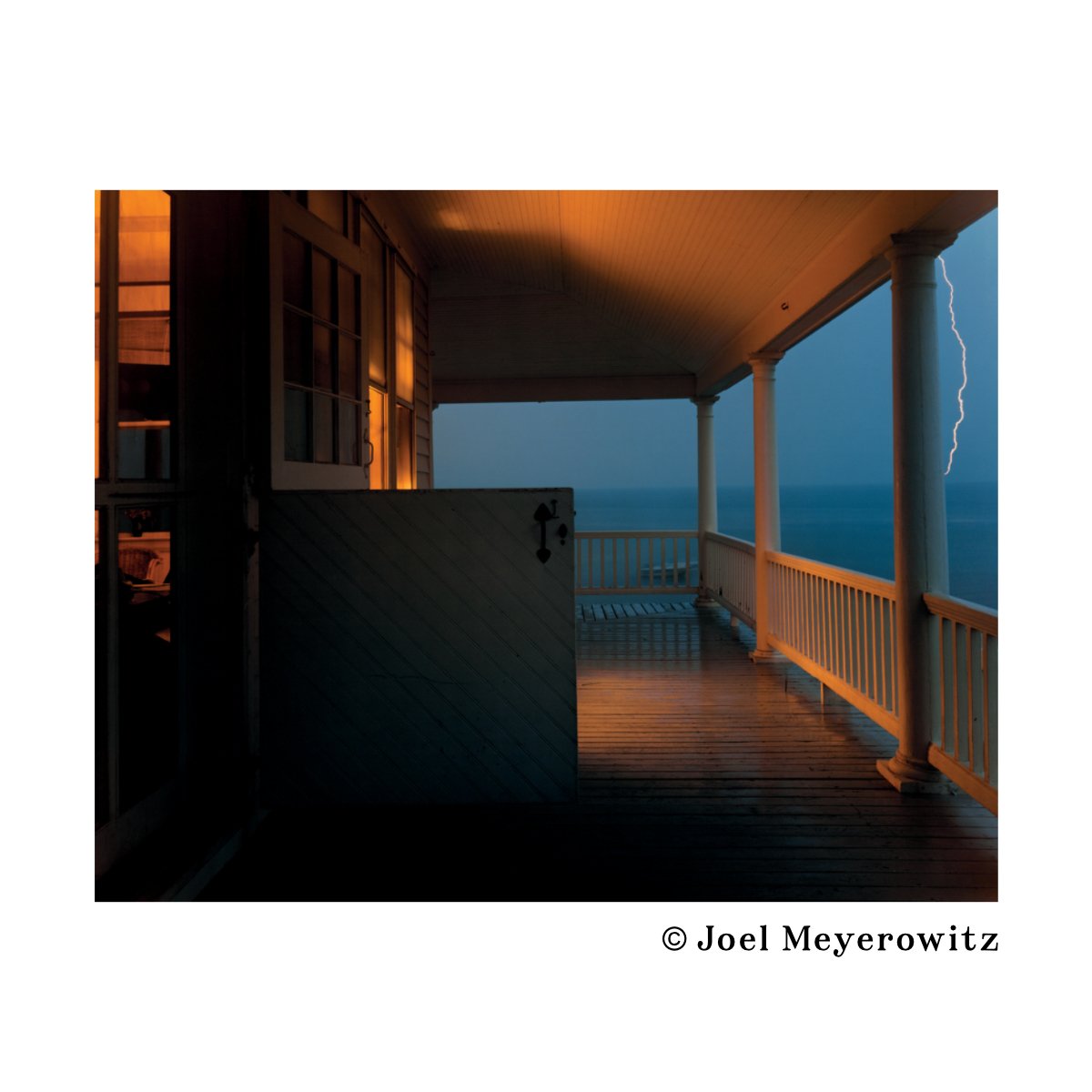

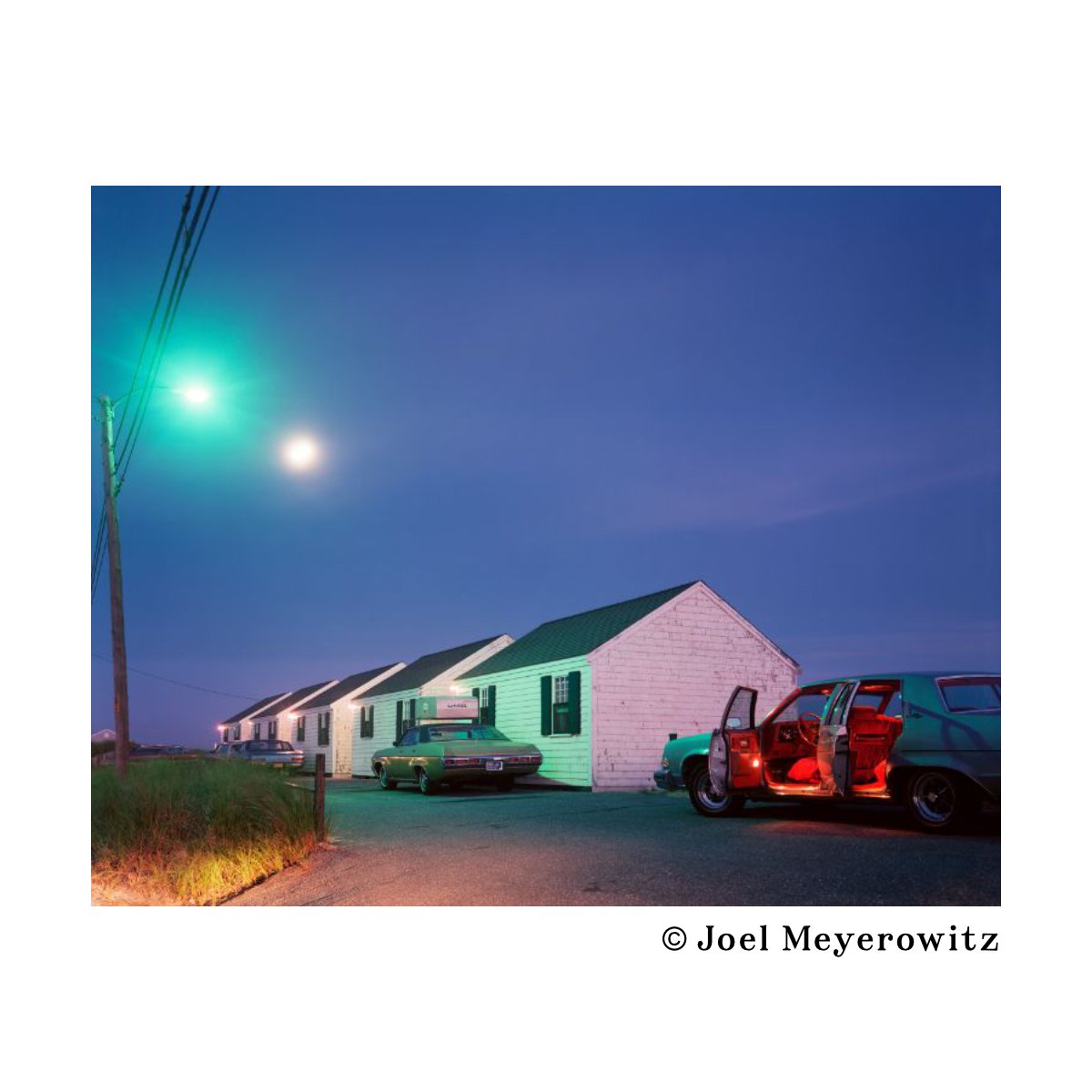

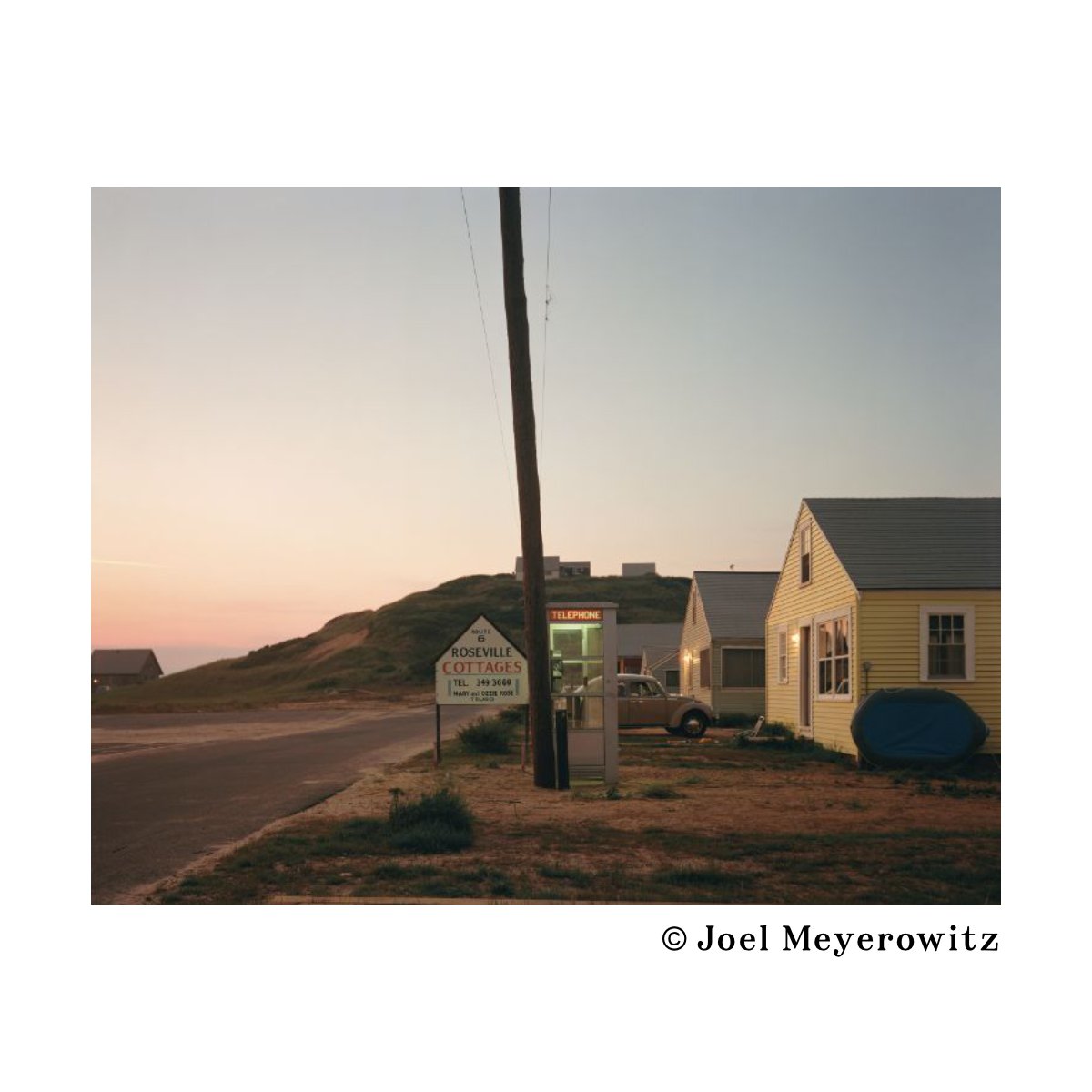

Out of this he created one of his more iconic works “Cape Light”.

Cape Light is a collection of images photographing Meyerowitz’s time in Cape Cod.

And many of the images are both calm and dynamic, scenic and captivating.

I actually found this book in a used bookstore for a pretty cheap price, so I had to pick it up.

More than the images he produced, what I took from Meyerowitz was the way he went about things.

He began working on Cape Light in 1976.

Meyerowitz began photographing in roughly 1962.

That’s a whole 14 years apart.

And it shows that it’s never too late to switch gears and completely reinvent yourself as a photographer, not only genre wise but also the entire system you’re shooting on.

Similarly, I learned the importance of not boxing yourself in.

Cape Light was by no means striking street photographs in the middle of New York.

Rather the tones are peaceful, calm, and aesthetic.

It felt like Meyerowitz simply fell in love with this town, wanted to take pictures of it, and made a book around it.

The same applies for whatever you or I want to create.

The subject doesn’t have to be grand, world level, or world changing.

Just find something you’re attracted to and create around that.

This way, even if you’ve never been to Cape Cod, if done well, the images taken by the photographer will make it feel like you have.

Good work can reveal the same emotions, feelings, and ideas the photographer was experiencing at the time.

So photograph whatever you want to photograph and use that to create whatever project you want to create.

It doesn’t have to be what’s popular - the subject is chosen by you after all.

And if you feel that compulsion towards something, even if it’s not trending, it’s in your best interest to pursue or capture it.

That’s the sort of indirect lesson I’ve taken from flipping through Meyerowitz’s book.

It helped give me that extra piece of permission: because he did this, I don’t feel wrong about doing this.

Tony Vaccaro and Loss

Tony Vaccaro, I’ve talked about before, was well known wartime photographer.

And he documented much of WWII, post war occupation in Germany.

In his book, Entering Germany, he details how an accident happens and he loses almost all or the majority of his work.

This was in 1947 and roughly 4000 film images were lost to the void, never to be published or seen again.

And undoubtedly many of these images were iconic, each sharing a space in time which won’t be replicated.

Despite this, he continued to photograph, amassing nearly 10,000 images by the end of his time in Germany.

I think the great takeaway here is: accidents happen.

Even if you’re the most careful photographer, your hard drives can go bust, your raids can malfunction, and the house can burn down.

So the fact of the matter is, everything can and will one day be lost.

It might not happen while you’re alive, but nothing escapes father time.

And if you or I do stumble upon the unfortunate occurrence of loss, remind yourself: it wasn’t a complete waste of time.

Maybe we lost all the photos we took for the past decade.

The trips, the memories - things that will never happen again.

But what we didn’t lose was the skill, the knowledge, the understanding of photography we’ve built up over the years.

That can’t be taken away from us, no matter how many hard drives burn.

The rebuilding of a new archive or catalog can be a dismal venture.

But the archive we’ve amassed over the years wasn’t the point.

The point of all the work we’ve put in was to build up us - as photographers, artists, creatives.

We are the real thing we’ve been working on this whole time.

And “starting over” won’t actually be starting over.

Like a video game, we’ll be able to clear the early levels with ease, because we’ve done it before.

If you have the skill, the photos will come.

Maybe not the same exact ones.

Maybe not the exact tones, colors, or moments.

But the photos will come.

At the end of the day, studying the greats has taught me a lot about photography.

This wasn’t meant to be a comprehensive list of every great photographer, but rather just a few I’ve taken notes from.

What’s interesting to me is how relatable many of the lessons we take from others can be.

I’m nowhere near the level of these guys and I don’t care to be.

And my photography and subject matter isn’t the same either.

But it doesn’t matter, because what I’ve learned from them still applies and still helps.

Cartier Bresson’s lesson about composition, I learned independently on my own.

Composition comes from following the eye, any analysis is post-mortem.

I had the same thoughts and ideas and reading his essay gave me the confirmation I needed.

The same goes for Joel Meyerowitz.

Seeing his work gave me that extra bit of reassurance: that I could switch gears, switch formats, and make whatever I want to make.

And through Tony Vaccaro, I was reminded that losing everything isn’t everything.

Because if you were to imagine taking pictures that entered the void as soon as you took them, the act of taking them is still rewarding in itself.

Leave a comment on the YouTube video of a photography lesson you’ve learned from someone either directly or indirectly.

It doesn’t have to be from someone famous - they say you can learn from anyone, even a child.

And if you found this article helpful, please share this with a friend who could also benefit from this.

You can also learn more in Photography Essentials in the link - it’s free.

And be sure to pick up a copy of “The Sinking Sun”, my zine, prints, and shirts in the links here.

Thanks for reading, happy shooting.